While focusing on a section of AfuriKo’s recent arrangement of “Kassai” during practice yesterday, I came across a mi7(b5) chord that calls for the locrian chord scale. Remembering Frank Mantooth’s approach in his Voicings for Jazz Keyboard inspired me to research possible 5-note 2-hand voicings for this chord.

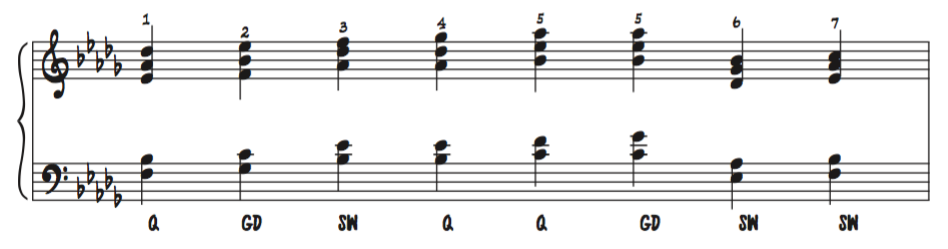

So let’s quickly jot down a major scale and list all possible Quartal (Q), Generic Dominant (GD), and So What (SW) voicings that can be built under each scale degree (top note):

The results are summarized in the table below:

| voicing type | top note |

|---|---|

| Quartal | 1, 4, 5 |

| Generic Dominant | 2, 5 |

| So What | 3, 6, 7 |

The next step is to find suitable candidates to aurally represent our half-diminished locrian chord! It feels natural to go with those that:

- sound best individually when trying them out against the root (C in the key of Db major) in the low register of the keyboard;

- sound best in the context of a minor II-V-I.

You’ll notice that most of the eligible voicings include all three guide tones (namely b3, b5, and b7), which seems coherent since these notes characterize the mi7(b5) sound. One of the voicings, however, features b3 and b7 only (no b5), but still sounds strong as a mi7(b5) chord (to my ears…) so I went ahead and included it here, too.

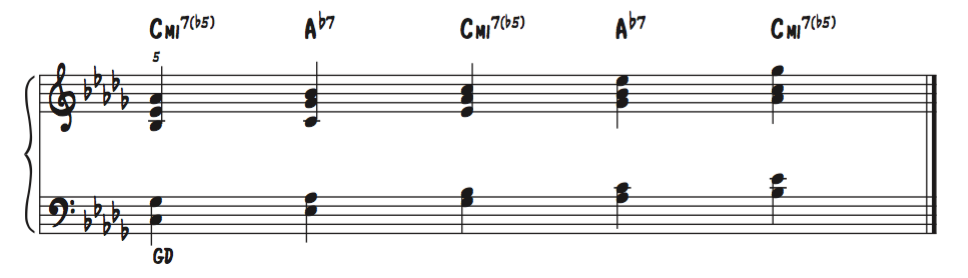

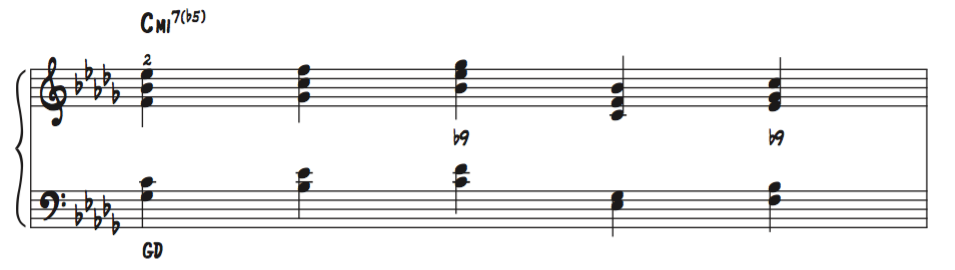

1) The Generic Dominant voicing built underneath scale degree 2 has all four chord tones (C, Eb, Gb, Bb) and the 11th (F). Here it is notated below followed by its four inversions:

Two of these inversions contain the interval of a b9. They sound dissonant and not quite appropriate for a mi7(b5) chord, so let’s go ahead and rule them out. We are left with the following three solid-sounding voicings for Cmi7(b5). From the top note down:

- Eb Bb F C Gb

- F C Gb Eb Bb

- Bb F C Gb Eb

Incidentally (or not!), these notes make up the F insen pentatonic (F Gb Bb C Eb), which reveals itself as a very interesting scale to solo over Cmi7(b5).

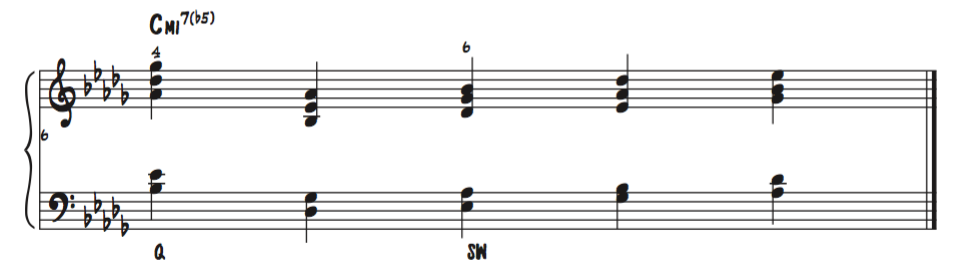

2) The So What voicing built underneath scale degree 3 is slightly more adventurous, containing only two of the guide tones (Bb and Eb) and three tensions: the b9th (Db), the 11th (F), and the b13th (Ab). Its inversions don’t seem to function so well (again, these perceptions are of course subjective and there are no hard and fast rules…) as a mi7(b5) chord so let’s just keep the following chord, from the top note down:

- F Db Ab Eb Bb

Now, it turns out this particular set of notes corresponds to the Db major/Bb minor pentatonic, which is thus also a valid choice to solo over Cmi7(b5).

3) The Generic Dominant voicing built under scale degree 5 contains all four chord tones (C, Eb, Gb, Bb), as well as the b13th (Ab). Here it goes with its inversion:

Two of the those voicings (labeled Ab7 above) have a very distinct dominant color, but we can definitely use the other three as strong sounding half-diminished locrian chords. Spelling them from top to bottom, we have:

- Ab Eb Bb Gb C

- C Ab Eb Bb Gb

- Gb C Ab Eb Bb

These notes (Ab Bb C Eb Gb) constitute the Ab dominant pentatonic scale.

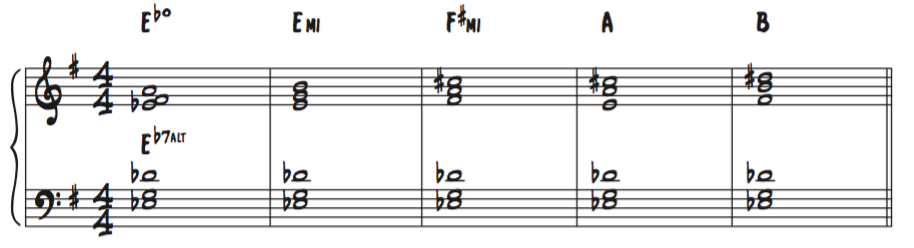

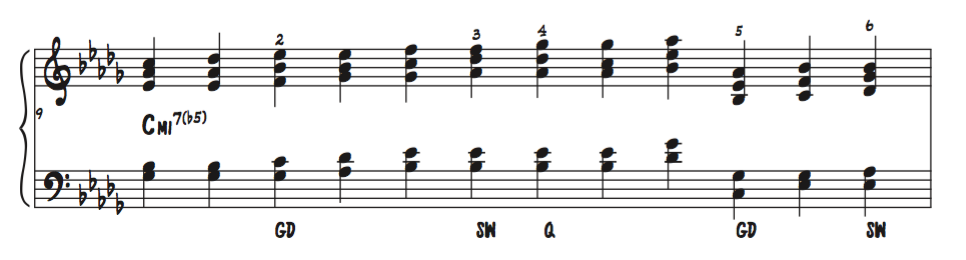

4) The Quartal voicing built under scale degree 4 and the So What voicing built under scale degree 6 are in fact inversions of each other:

Although the Db here creates the interval of a b9 with the underlying root (C), it is OK to go ahead and list all inversions for this chord as possible mi7(b5) voicings because b2 is a characteristic note of the locrian mode. From the top note down, we have the following five additional possibilities for Cmi7(b5):

- Gb Db Ab Eb Bb

- Ab Eb Bb Gb Db

- Bb Gb Db Ab Eb

- Db Ab Eb Bb Gb

- Eb Bb Gb Db Ab

This last set of notes uncovers the Gb major/Eb minor pentatonic, yet another option to solo over Cmi7(b5).

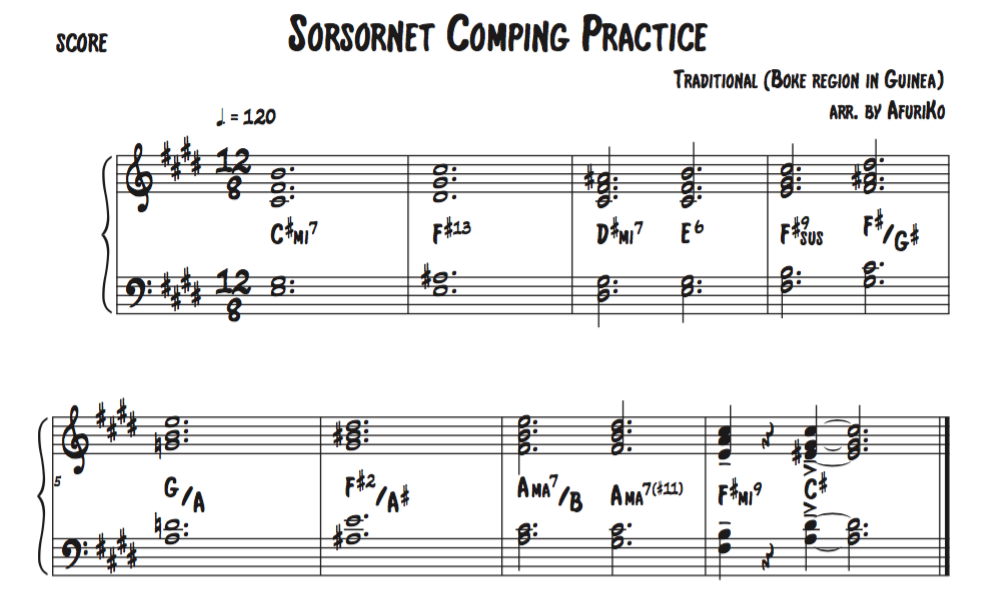

To sum up, here are all twelve previously found half-diminished locrian voicings:

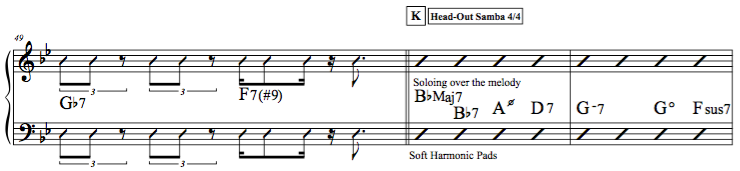

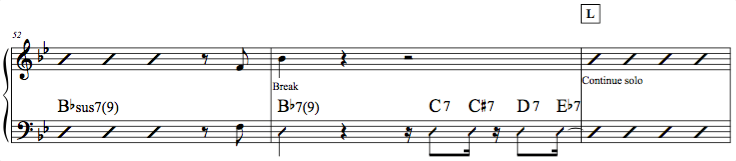

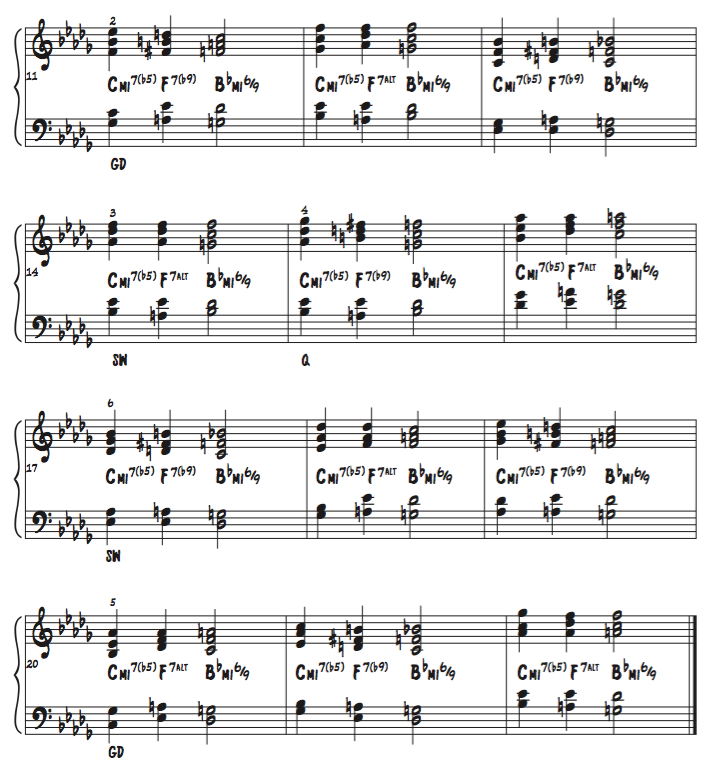

And finally, let’s put them back in context! I have chosen minor II-V-Is with either V7(b9) or V7alt as the dominant chord:

ADDENDUM

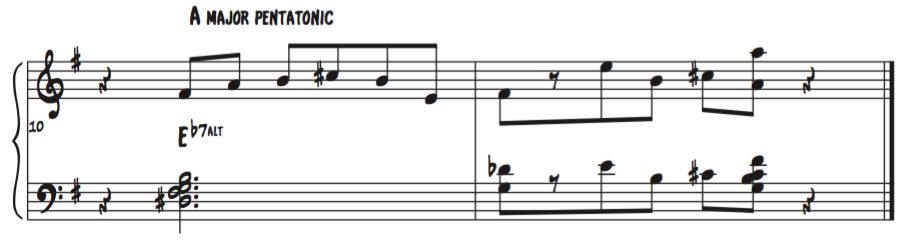

29 Oct. 2019

The in pentatonic scale (E F A B D) is also contained within the major scale and can also be used effectively to derive 5-note 2-hand voicings for half-diminished locrian chords (Bmi7(b5) in this case). The way to do it is to play the first scale degree (E), skip the second scale degree (F), play the third scale degree (A), skip the fourth scale degree (B), etc… until you’re playing all five notes simultaneously, divided between both hands. You will end up with the voicing E A D F B, and its inversions (F B E A D, A D F B E, B E A D F, and D F B E A). Some of these include the interval of a b9 within the voicing (between the notes E and F) but this doesn’t matter (in my opinion and experience) as the flatted second scale degree is a characteristic note of the locrian mode.

Visit http://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today: