Review (in French) of Jim Funnell’s Word Out’s second studio album Spirit of the Snail on jazz critic Guillaume Lagrée’s blog Le jars jase jazz (also available on paperblog.fr).

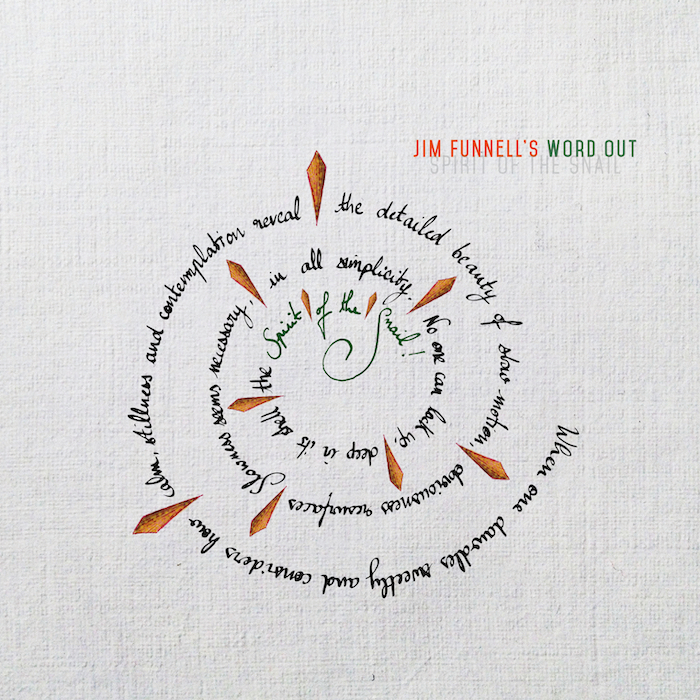

Jim Funnell’s Word Out

“Spirit of the Snail”

Produced by Jim Funnell

Released on Tuesday, 22 September 2015

CD release concert at the Sunside in Paris at 7.30pm on Tuesday, 22 September 2015.

Jim Funnell: piano and compositions

Oliver Degabriele: acoustic bass

Thibault Perriard: drums

Isabelle Oliver: harp

“Dear cosmopolitan and xenophile readers,

As you know, the EU motto is “United in diversity.” As far as politics are concerned, it remains to be proved. On the subject of music however, British pianist Jim Funnell, Maltese bassist Oliver Degabriele, and French drummer Thibault Perriard illustrate it perfectly every time they play together. I have already praised their music in concert and in the studio. On this album, the triad is augmented with the presence of harpist Isabelle Olivier. She is nor a feminine alibi for a masculine trio, neither a classical one for a jazz trio. Her harp sounds like the kora of a Mandinka master.”

“[ Jim Funnell’s ] music is the singular result of a thorough reflection on rhythms, sounds, and colors.”

“Whether you want to stimulate your ears, your brain, or get your limbs in motion, enter the Spirit of the Snail with Jim Funnell and his band!”

– Guillaume Lagrée