Such a Sweet Dawdle on Neon Jazz (playlist by Joe Dimino)

pentatoniques : les bases

Le terme “pentatonique” nous vient de la langue grecque : le préfixe penta-, “cinq”, et le mot tonos, “ton”, y sont associés pour évoquer l’idée d’une gamme à cinq notes.

Il existe bien entendu de nombreuses possibilités d’échelles de cinq sons au sein du système tempéré (division de l’octave en douze intervalles égaux, dits chromatiques). Nous porterons ici notre attention sur la gamme pentatonique la plus usitée et l’appellerons la pentatonique “globale”¹ (on retrouve en effet cette gamme dans les musiques de nombreuses cultures de par le monde).

[1] La pentatonique globale est fondée sur une succession de quintes ascendantes : do sol ré la mi.

[2] Une fois ces notes réarrangées au sein d’une seule octave, nous avons : do ré mi sol la.

[3] Les intervalles formés par les notes de cette gamme par rapport à sa fondamentale (do) sont :

- une seconde majeure entre do et ré ;

- une tierce majeure entre do et mi ;

- une quinte juste entre do et sol ;

- une sixte majeure entre do et la.

Comme tous les intervalles de cette gamme sont majeurs (mis à part la quinte juste), elle est souvent baptisée pentatonique majeure. Ce que j’appelle sa “formule”, qui associe des chiffres arabes² à chacun de ses degrés (contrairement aux chiffres romains communément utilisés pour représenter les accords construits sur chacun des degrés d’une gamme), est la suite de nombres : 1 2 3 5 6.

[4] Exactement comme pour les échelles majeures diatoniques à sept sons (do ré mi fa sol la si), la gamme relative mineure de la pentatonique majeure se construit en jouant toutes les notes formant la pentatonique majeure, en partant une tierce mineure en dessous de la fondamentale de celle-ci : la do ré mi sol.

[5] Les intervalles formés par les notes de cette nouvelle gamme par rapport à sa fondamentale (la) sont :

- une tierce mineure entre la et do ;

- une quarte juste entre la et ré ;

- une quinte juste entre la et mi ;

- une septième mineure entre la et sol.

Comme tous les intervalles de cette gamme sont mineurs (sauf la quarte et la quinte), elle est souvent appelée pentatonique mineure. Sa “formule” est : 1 b3 4 5 b7.

En résumé, voici les formules à savoir (accompagnées d’exemples ayant la note do pour tonique dans les deux cas pour faciliter la comparaison) :

| Pentatonique majeure | 1 2 3 5 6 | do ré mi sol la |

| Pentatonique mineure | 1 b3 4 5 b7 | do mib fa sol sib |

Notes

¹ Cette terminologie est utilisée par Michael Hewitt dans son livre Musical Scales of the World (voir Hewitt 2013).

² Plus exactement, il s’agit des chiffres communément utilisés en Europe qui nous viennent du système de numérotation indo-arabe.

Références

Hewitt, Michael. “Section 5: Pentatonic Scales.” Dans Musical Scales of the World, 125-134. The Note Tree, 2013.

pentatonics: the basics

🇫🇷 → pentatoniques : les bases

The term “pentatonic” comes from the Greek language: the prefix penta-, “five,” and the word tonos, “tone,” are associated to bring forth the idea of a five-tone scale.

There are of course many five-tone scale possibilities within the twelve-tone equal temperament system. We’ll focus on the most common pentatonic scale here and call it the “global” pentatonic¹ (this particular scale is indeed encountered in the musics of many cultures around the world).

[1] The global pentatonic is based on a succession of ascending fifths: C G D A E.

[2] Reordered within the range of a single octave, we have: C D E G A.

[3] The intervals formed by the tones of this scale relative to its root (C) are as follows:

- a major second between C and D;

- a major third between C and E;

- a perfect fifth between C and G;

- a major sixth between C and A .

Since all the intervals in this scale are major (except the perfect fifth), it is often referred to as the major pentatonic. What I call the scale’s “formula,” based on Arabic numerals² representing its scale degrees (as opposed to Roman numerals commonly used to represent chords that are built on each scale degree), is: 1 2 3 5 6.

[4] Just like the diatonic seven-note major scale (C D E F G A B), the major pentatonic’s relative minor scale can be built by playing all the notes that comprise the major pentatonic, beginning on the tone located a minor third below the latter scale’s root: A C D E G.

[5] The intervals formed by the tones of this new scale relative to its root (A) are as follows:

- a minor third between A and C;

- a perfect fourth between A and D;

- a perfect fifth between A and E;

- a minor seventh between A and G.

Since all the intervals in this scale are minor (except the perfect fourth and fifth), it is often called the minor pentatonic. Its “formula” is: 1 b3 4 5 b7.

To sum up, here are the important formulas again below (accompanied by examples with the note C as the tonic in both cases, for ease of comparison):

| Major pentatonic | 1 2 3 5 6 | C D E G A |

| Minor pentatonic | 1 b3 4 5 b7 | C Eb F G Bb |

Notes

¹ This terminology is used by Michael Hewitt in his book Musical Scales of the World (see Hewitt 2013).

² More accurately speaking, these are the numerals commonly used in Europe that stem from the Hindu-Arabic numeral system.

References

Hewitt, Michael. “Section 5: Pentatonic Scales.” In Musical Scales of the World, 125-134. The Note Tree, 2013.

Live in Japan: A Neon Jazz interview with host Joe Dimino

the “dominant shape” – part 1: major and melodic minor

A multifaceted structure

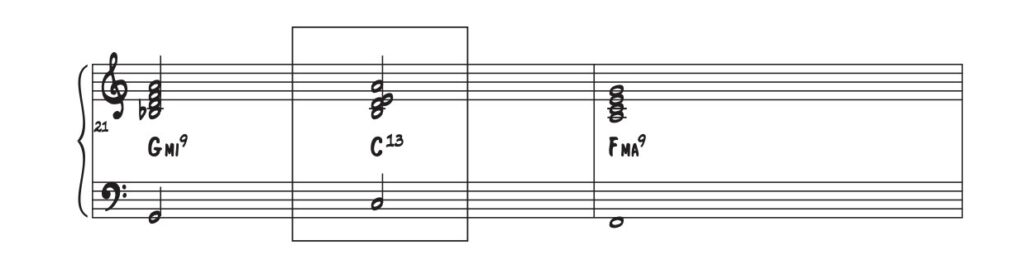

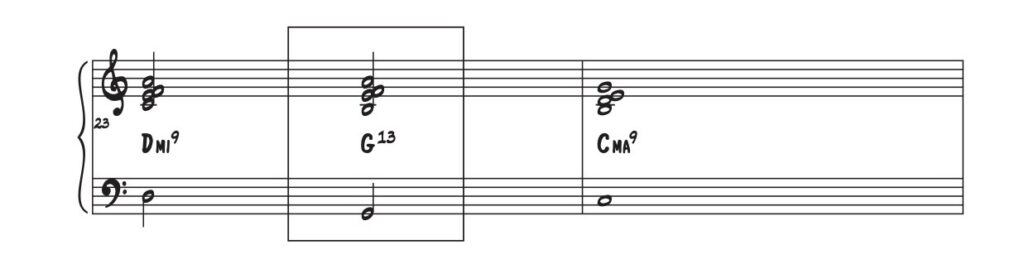

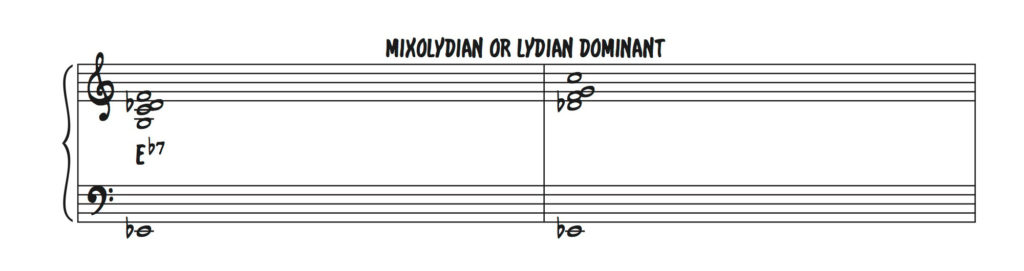

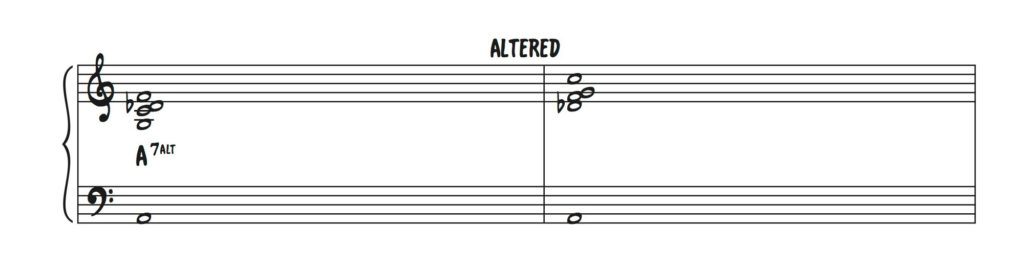

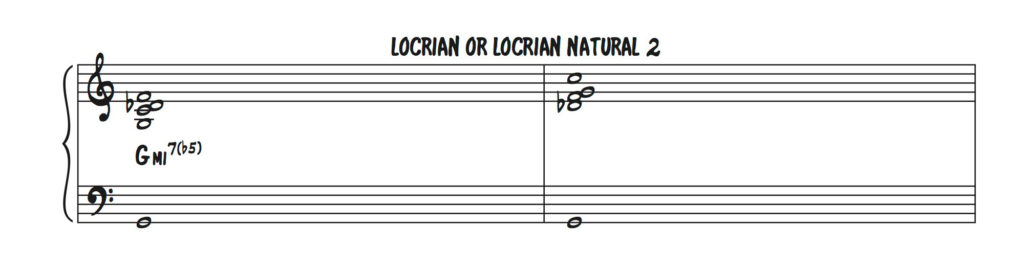

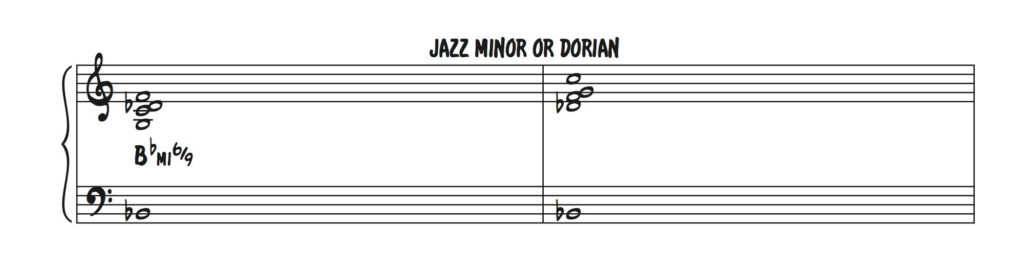

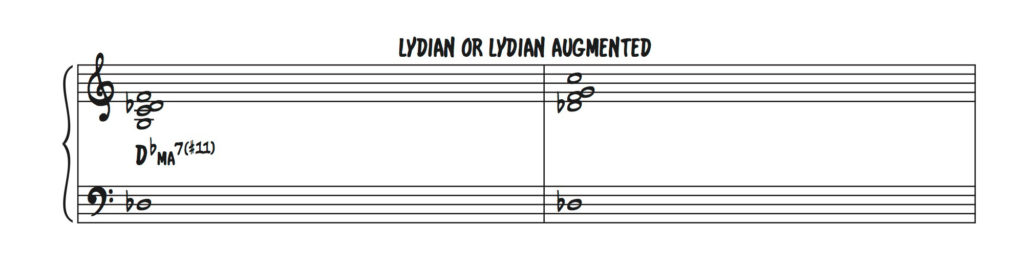

The “dominant shape” is extremely versatile. It can be used to voice chords that are derived both from major harmony, and from melodic minor harmony. The degrees on which each chord mentioned here functions are indicated in the captions below each example. Some of those chords work better in modal contexts (or when one has a vertical approach on each particular chord within a tonal context), and some also sound fitting in various tonal contexts. Let your ear be your guide!

Transposable formulas (specific arrangements of chord tones and tensions, e.g. “3 13 b7 9”) are also given in the captions for each chord (in each caption, position B is listed first and position A second to be consistent with the music notation). By position A/B, it is meant “dominant shape (voicing used for the V chord) extracted from the major II-V-I progression in position A/B.”

The dominant shape is comprised of the following intervals (listed from the bottom to the top of the voicing): major third, major second, perfect fourth in position A / perfect fourth, minor second, major third in position B.

Use cases

The mixolydian chord is listed here in prime position, since it is, naturally, the one from which the thought of using the dominant shape to play other chords initially came from. As you will see in the first example below, the lydian dominant or 7(#11) chord, from melodic minor, can be voiced in the exact same way as the mixolydian chord (even though the colourful #11 won’t appear in this specific voicing). Then we have the altered chord, and it is interesting to note that there is a sub V (tritone substitution) relationship between the mixolydian and the altered dominant chords. Eb7 and A7alt, for example, indeed share the same guide tones (G and Db/C#), and their roots are indeed a tritone apart. As a result, one chord can be substituted for the other following the tritone substitution rule.

Position B: 3 13 b7 9; Position A: b7 9 3 13.

Position B: b7 #9 3 b13; Position A: 3 b13 b7 #9.

I have then chosen to list the locrian/locrian natural 2 and dorian/jazz minor chords, since they are also widely used. In fact, a minor II-V-I can be played entirely using the dominant shapes presented here (e.g. Emi7(b5) = E A Bb D, A7alt = G C Db F, Dmi6/9 = F A B E).

Position B: 1 11 b5 b7; Position A: b5 b7 1 11.

Position B: 6 9 b3 5; Position A: b3 5 6 9.

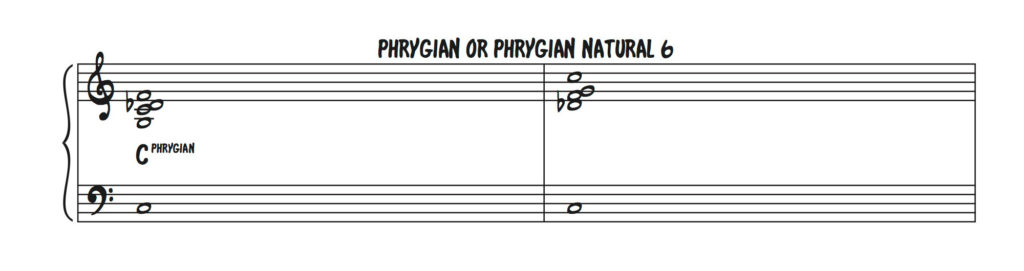

Next up are the lydian/lydian augmented and phrygian/phrygian natural 6 sounds, which also come in handy, albeit arguably more sporadically than the ones mentioned previously.

Position B: #11 7 1 3; Position A: 1 3 #11 7.

Position B: 5 1 b9 11; Position A: b9 11 5 1.

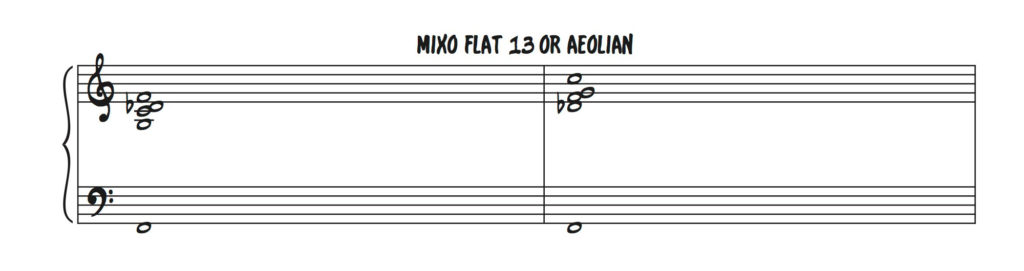

The mixolydian b13/aeolian sound is probably the least common of all (moreover, it is rather tricky to find an adequate chord symbol for it, so the space has been left blank).

Position B: 9 5 b13 1; Position A: b13 1 9 5.

Finally, if the same voicing (G C Db F in position B / Db F G C in position A) were to be played over an Ab root (tonic of the Ab major scale) in order to obtain an ionian sound, the “avoid note” Db might stand out and create havoc, particularly in a tonal context… In a modal/vertical context however, the voicing can be used and sounds quite unique and intriguing.

Practice tip

Internalize both shapes by taking them through the cycle of fifths (using different roots in the left hand for example; that way you’ll get the different sounds described above). It’s fine if you have to think about the formulas at first, but try and gradually shift towards using your ears and muscle memory exclusively. It is without question a challenging exercise… But trust yourself in the process: it will be way more fun!

Live in Japan album review: All About Jazz

🇺🇸/🇬🇧 “Word Out … takes its name from Rainer Maria Rilke’s observation that “most experiences are unsayable.” Even so, it’s a heck of a lot of fun when they can be played instead.”

🇫🇷 “Word Out … tire son nom de l’observation de Rainer Maria Rilke selon laquelle “la plupart des expériences sont inexprimables”. Néanmoins, quelle joie de pouvoir les entendre jouées à la place !”

Geno Thackara, All About Jazz

arpeggiating altered chords

Piano being a polyphonic instrument, pianists naturally have access to playing several notes on the keyboard at once, which is definitely an advantage when trying to develop harmonic consciousness. Guitarists also have a fretboard suited to playing and hearing both simple and complex chords, and vibraphonists, with two pairs of sticks, are often seen playing four notes at once — a perfect number if you’re focusing on chord tones only! But what about you melodic instrumentalists out there? How does a flute player, a trumpet player, or a double bass player go about hearing a tune’s harmonic framework?

Having taught a few people who play such melodic instruments (as opposed to pianists which typically make up the bulk of my students), I have found that going through a tune arpeggiating its chords is a worthwhile exercise. It gives the player a deeper awareness of the changes, which later enables him or her to be more connected to the tune when improvising (and when playing/embellishing the melody).

Arpeggiating is easily achieved for most chords: play the chord tones first (root, third, fifth, and seventh) then move up to the tensions (ninth, eleventh, and thirteenth)¹. Once you’ve reached the top, just make your way back down from the thirteenth to the root. That works really well for major and minor chords with ninths, elevenths, and thirteenths, and also for most dominant chords with tensions. But altered chords (a specific kind of dominant chord) can be a bit of a challenge because of the inner workings of the altered mode: it indeed appears to have two ninths (one flat and one sharp), and can be apprehended as having two fifths as well (a diminished and an augmented fifth). This can all be quite confusing… So let’s try and see through the fog so that you know what to play when you get to those last four bars of the tune Footprints for example².

First, it is important to know that the altered chord’s parent mode, the altered mode, comes from the melodic minor scale (also called jazz minor). Play C melodic minor for instance (C melodic minor is equivalent to the C major scale with a minor third instead of a major third). Now play all the same notes as in C melodic minor, but starting and ending on the note B. This is the B altered mode (B C D Eb F G A B), mode VII of melodic minor (the altered chord is thus the VIIth degree of melodic minor). Now, let’s attribute scale degrees (notated using Arabic numerals accompanied by flats and sharps when necessary) to the notes of the B altered mode:

| B | 1 | root |

| C | b9 | flat ninth |

| D | #9 | sharp ninth |

| Eb (= D#) | 3 | major third |

| F | b5 / #11 | diminished fifth or sharp eleventh |

| G | #5 / b13 | augmented fifth or flat thirteenth |

| A | b7 | minor seventh |

If you look closely, you might notice that we seemingly have two different kinds of thirds in this mode: a minor third (D), and a major third (Eb or, spelled enharmonically, D#). Theoretically, D natural can also function as a #9 on a chord whose root is B. And since we cannot have two thirds in a given chordmode³, scale degrees 3 and #9 can logically be attributed to D# (Eb) and D respectively.

We have now identified three of our chord tones: the root (B), the major third (D#), and the minor seventh (A), which indeed outline a dominant seventh chord in skeletal form. It’s now time to add some flesh to those bare tones! Before moving on to tensions, we have to make a choice for our last chord tone: the fifth. We can either use a diminished fifth (the note F in our example) or an augmented fifth (G).

Altered arpeggio using b5 as a chord tone

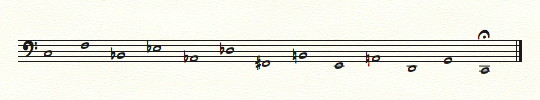

If we decide that the b5 will function as the fifth of the altered chord for our purpose of arpeggiating it, we have the notes B, D#, F, and A in the lower part (chord tones) of the arpeggio. The remaining notes of the chordmode are C (b9), D (#9), and G (b13). They form the upper part (tensions) of the arpeggio. And we have:

| B | D# | F | A | C | D | G | D | C | A | F | D# | B |

| 1 | 3 | b5 | b7 | b9 | #9 | b13 | #9 | b9 | b7 | b5 | 3 | 1 |

Notice that the tensions (C, D, and G) form a quartal triad that can be notated C2, D7sus(omit 5), or Gsus depending on its inversion. In this case, there is an absence of eleventh in the chordmode due to the presence of b5.

Altered arpeggio using #5 as a chord tone

If we decide that the #5 will function as the fifth of the altered chord for our purpose of arpeggiating it, we have the notes B, D#, G, and A in the lower part (chord tones) of the arpeggio. The remaining notes of the chordmode are C (b9), D (#9), and F (#11). They form the upper part (tensions) of the arpeggio. And we now have:

| B | D# | G | A | C | D | F | D | C | A | G | D# | B |

| 1 | 3 | #5 | b7 | b9 | #9 | #11 | #9 | b9 | b7 | #5 | 3 | 1 |

The tensions (C, D, and F) do not form any specific tertial nor quartal triad here, and in this second scenario, there is an absence of thirteenth in the chordmode due to the presence of #5.

So there you have it: two different ways of arpeggiating altered chords in full (i.e. entire chordmodes with four chord tones and three tensions). Don’t forget to practice both examples a) and b) in all twelve keys! As always, I recommend following cycle five root motion, starting at different points in the cycle every time you pick up your instrument to practice (I’ve started with B7alt in the audio examples above since this is the chord we’ve been concerned with throughout the article).

Finally, to further illustrate my point, allow me to offer a recording of Footprints for your consideration, wherein I used seven-note voicings extensively in the keyboard part (stacked thirds for the most part and the altered voicings discussed above for E7alt and A7alt in the 10th measure of each chorus). The track features soloists Corey Wallace (trombone) and Philippe Lopes De Sa (soprano saxophone), as well as a rhythm section comprised of Akiko Horii (percussion), Hiroshi Fukutomi (electric guitar), and myself (keyboard and keyboard bass). Enjoy!

Notes

¹ These kinds of voicings are often referred to as “stacked thirds” (Levine 2014:3)

² The chords in this four bar progression are F#mi7(b5), F7(#11), E7alt, A7alt resolving to Cmi7. Listen to Wayne Shorter’s version on Adam’s Apple.

³ A chordmode is an indivisible entity that arises when a given chord sounds in unity with the scale from which it derives. “The complete sound of a chord is its corresponding mode within its parent scale.” (Russell 2001)

References

Levine, Mark. “Chapter One: The Menu.” In How to Voice Standards at the Piano: The Menu, 1-22. Petaluma: Sher Music Co., 2014.

Russell, George. “Part One: The Theoretical Foundation of the Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization.” In Lydian Chromatic Concept of Tonal Organization – Volume One: The Art and Science of Tonal Gravity, 1-53. Brookline: Concept Publishing Company, 2001.

Shorter, Wayne. Adam’s Apple. Blue Note 7464032. 1987 (originally released in 1966).

Visit http://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today:

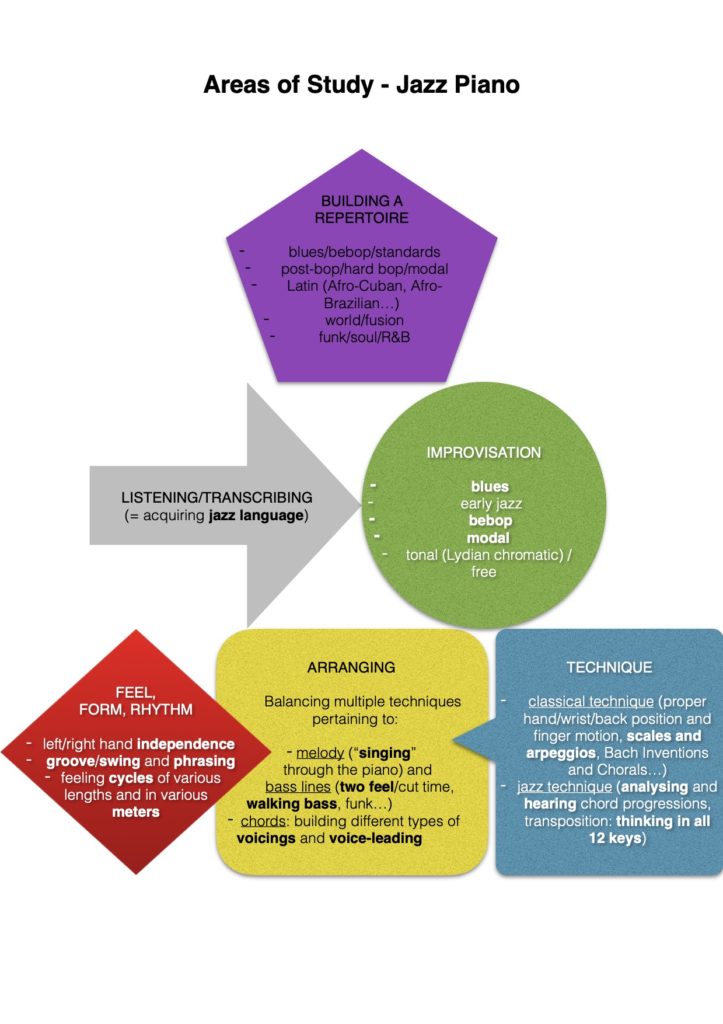

the six building blocks of jazz piano playing (areas of study)

The foundational level

‘Feel, form, rhythm’, ‘arranging’, and ‘technique’ are what I call the three foundational blocks of jazz piano playing. Without them, you won’t be able to build anything musically solid because your playing will always lack rootedness, depth, and precision. To improve in the area of ‘feel, form, and rhythm’, I recommend immersing yourself in some kind of West African musical tradition¹ (Ewe drumming and dance, djembe and dundun rhythms, etc.).

‘Arranging’ is about mastering different textures and telling an engaging story. The piano has an inherent orchestral quality due to its wide range and polyphonic nature, so there is a lot to cover here, from bass lines, to chord voicings, all the way up to how to interpret and embellish a melody.

As far as ‘technique’ is concerned, some sub-areas are specific to jazz (such as practicing a snippet of music in a variety of keys) and others more peculiar to classical performance (using gravity and proper posture to get a great sound out of the instrument for example). This is why I often encourage my students to work on Hanon’s Virtuoso Pianist in Sixty Exercises, and the Bach Chorales² and Two-Part Inventions at the very least (taking separate classical piano lessons altogether, in addition to the jazz piano lessons, being the ideal scenario).

The heartbeat of jazz

These first three foundational blocks support those that make up the second level in the diagram. ‘Improvisation’, in my opinion, is the heartbeat of jazz. It’s at the very core of the music, which itself is all about individuation (or finding your own voice). At its left, you’ll notice that I represented ‘listening/transcribing’ as an arrow pointing towards ‘improvisation’. That is because the jazz language you will be exposed to, and eventually internalize, will unavoidably feed into your personal style as an improviser (Wernick 2010). The elements of tradition and innovation constantly and dynamically coexist in jazz, very much like the yin and yang components of Taoist philosophy.

Culmination

Finally, all five aforementioned blocks support the final block at the top of the diagram: ‘building a repertoire’. Now the good news is: this task should be relatively effortless if you’ve studied all the other areas conscientiously… This culminating block is all about having fun learning the tunes you like, or even writing, practicing, and performing your own!

Notes

¹ I recall from my time at Berklee that such was also Meshell Ndegeocello’s advice.

² Jazz pianist Fred Hersch (2012) also recommends working on the Chorales, and offers a step by step approach to studying them involving pairs of two voices, then groups of three, and finally all four.

References

Bach, Jean-Sébastien. n.d. 101 Chorals à 4 parties réduction pour orgue ou piano. Paris: Editions Durand.

Bach, Johan Sebastian. 1970. Keyboard Music. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Dahn, Luke. 2021. “The Four-Part Chorales of J.S. Bach.” Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.bach-chorales.com/.

Hanon, Charles-Louis. 1929. Le Pianiste Virtuose en 60 Exercices. Bruxelles / Paris: Schott Frères.

Hersch, Fred. 2012. “Back to Bach: Keys to Jazz Piano Prowess.” Downbeat, September 2012 (pp. 76-77).

Wernick, Forrest. 2010. “The Importance of Language.” Jazzadvice. Posted June 30, 2010. https://www.jazzadvice.com/the-importance-of-language/.

Visit https://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today:

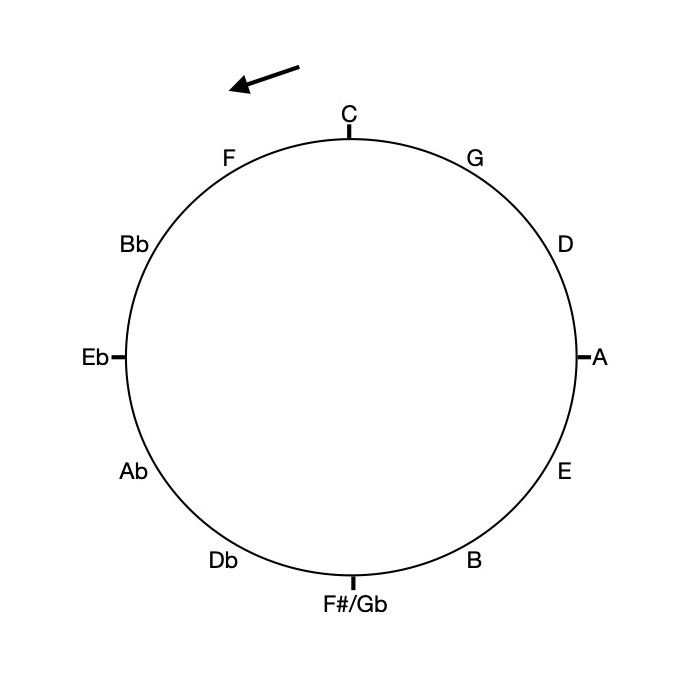

cycle 5 root motion: how to practice using the circle of fifths

As most of us musicians and music students know, the circle of fifths is notably helpful when figuring out what key a piece of music is in looking at its key signature. But it also has practical uses and can indeed be seen as the theoretical framework for what is commonly referred to as cycle 5 root motion. Cycle 5 root motion is often used as a way of traveling through all 12 pitches of the keyboard in order to work on anything, from a snippet of music to a whole tune, in all 12 keys. It also underpins the concept of the widely used II-V-I progression.

To go through the cycle, simply begin on any given note, go down a perfect fifth or up a perfect fourth (for a comprehensive review of intervals, click here) to reach the second note. Once there, repeat the process: go down a perfect fifth or up a perfect fourth and reach the third note. Repeat again, and again, and again… Until you are back at your starting point and have completed the cycle!

Oftentimes, you’ll see the circle of fifths starting and finishing on the pitch C (as in the example above). But you can of course begin and end at any point in the cycle. Actually, it might be a good idea to start at different points in the cycle every time you practice something in all 12 keys: repeated transposition can indeed be quite challenging and mentally exhausting, and more than once have I stopped half or a third of the way through the cycle, and forgotten where I left off the next day… So beginning on different pitches every time makes it more likely that you will eventually get through the whole cycle, or at least that you’ll cover some of the more unfamiliar keys!

When you start and end on C, unfamiliar keys (such as Ab, Db, Gb/F#, B…) are located towards “the middle” of the cycle, whereas the more familiar ones (fewer flats or sharps) are at “the beginning” and at “the end” (in quotation marks because a circle obviously has no beginning, no middle, and no end!). Beginning the cycle on say the pitch Ab is a way to ensure that you’ll venture through unfamiliar territory first during practice!