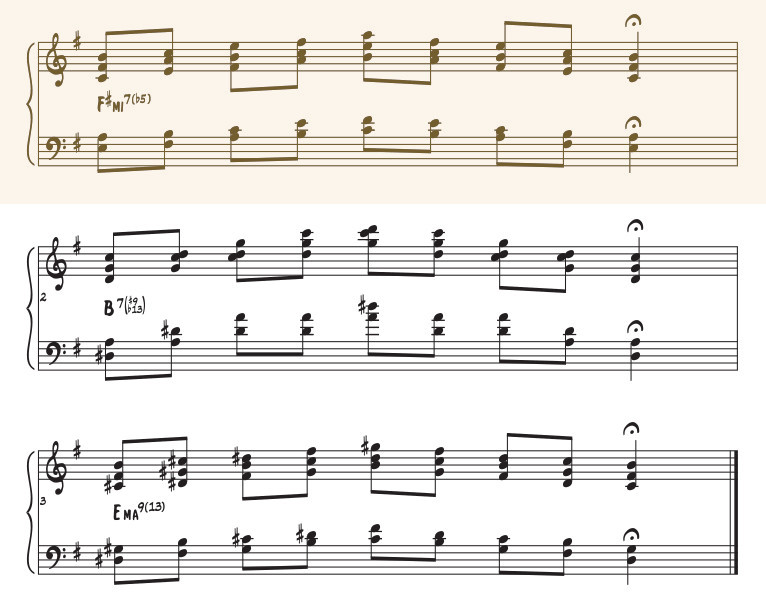

The example above is an exercise to practice some solid sounding 5-note voicings to play over a minor II-V that resolves to a Ima7 chord (just like in the second half of the bridge to All the Things You Are¹). So buckle up and get ready to take this whole thing through the cycle of fifths in all keys! You’ll hopefully end up with a brand new, hip sounding chord or two in your jazz piano toolbox…

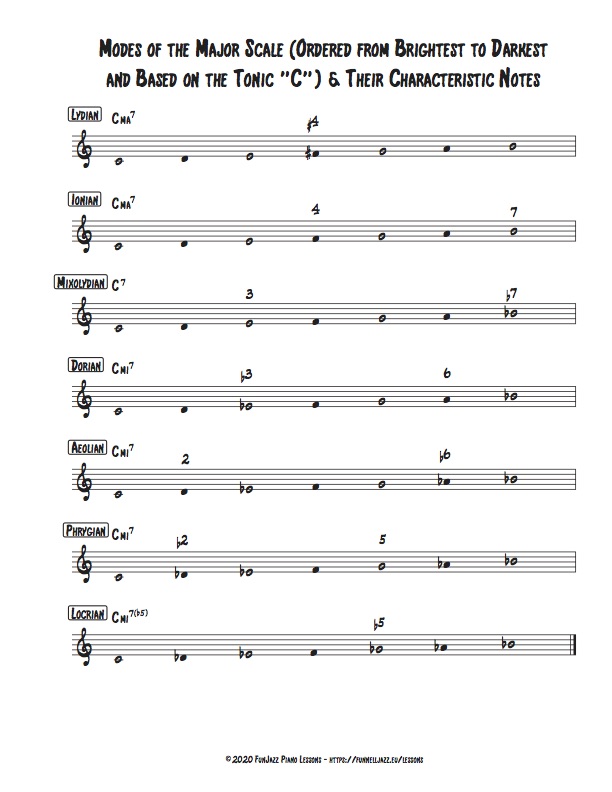

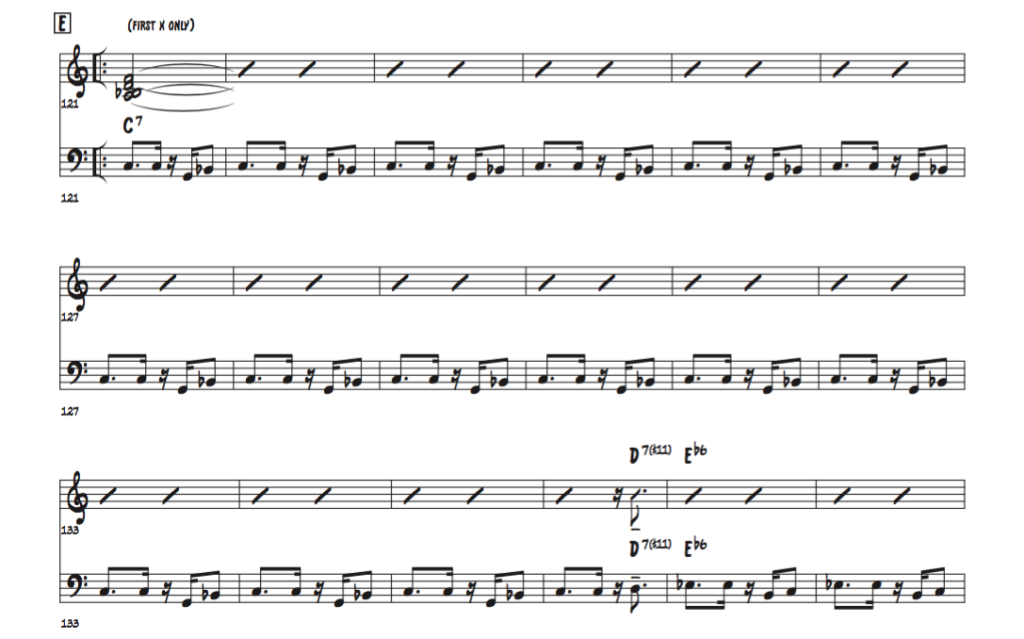

The first chord, F#mi7(b5), is built using what Mark Levine (1989) calls the insen pentatonic (B C E F# A – general formula: 1 b2 4 5 b7). You can construct the voicing yourself (without looking at the sheet music) by first playing an E below middle C (as the b7 of the chord, that E respects standard low interval limits), then skipping the F#, playing the A, skipping the B, playing the C, and so forth. In other words, playing every other note in the insen pentatonic scale and sounding all the notes together with both hands. As you can see from the example above, I have notated all five inversions of that chord (first ascending, and then descending all the way back to the inversion chosen initially). I find it very beneficial to practice in that fashion in order to create a “sheet of sound” effect, like McCoy Tyner comping for John Coltrane! Having all five versions of the chord under your belt will also enable you to voice lead as smoothly as possible in any situation, taking into account where you’re coming from and where you’re going harmonically. Lastly, if the tune you’re playing calls for dwelling on a certain chord for a somewhat prolonged amount of time (a few bars), there lies a perfect opportunity for you to explore some of those inversions for the sake of variation…

The second chord is a B7 to which we have added a b9, a #9, and a b13. These tensions form a C2 triad (C D G) which when inverted gives us either two perfect fourths stacked on top of each other (D G C), a Gsus triad (G C D), or a C2 triad (C D G)². Therefore we have an upper structure triad chord (UST) voiced with the aforementioned triad on top (played by the right hand) and the guide tones in the bottom (played by the left hand). To be musically consistent with the phrasing used for F#mi7(b5), I have included several “inversions” here too (to be precise, combinations of inversions of the top triad in the right hand with inversions of the guide tones in the left hand). Taken together, the five notes that make up the UST voicings used to voice this B7 chord also form an insen pentatonic (1 b2 4 5 b7), the tonic of which would be D (D Eb G A C).

The final chord, to which this progression resolves, is Ema7 (with thensions 9 and 13). The building process here is the exact same as for F#mi7(b5) (with the playing and skipping of every other tone in the scale), except that this time, a “regular”³ anhemitonic (containing no semitones) pentatonic is used (B C# D# F# G#). Do you notice how each individual voice outlines the pentatonic scale melodically? This also happened for the first chord of the progression, F#mi7(b5), which we also voiced using the play-and-skip-a-tone method applied to the insen pentatonic. On the contrary, playing through the different inversions of the B7 chord, voiced as an upper structure triad over its guide tones, is more choppy (with wider melodic intervals from one voicing to the next).

So there you have it: three solid sounding, 2-hand voicings for your minor II-V resolving to a major I chord. I hope you’ll enjoy practicing this snippet, and that it will prove to be a valuable addition to your harmonic vocabulary!

Notes

¹ Click here for a transcription (example #2) of guitarist Remo Palmieri soloing over the bridge of All the Things You Are (Gillespie 1993).

² Click here to see these quartal triads (2 and suspended) in root position and their inversions notated in treble clef.

³ In order to differentiate this particular pentatonic scale from other kinds of 5-note scales (such as the insen pentatonic mentioned earlier), I usually refer to it as “global.” After all, it “has been found in use upon every single continent of the planet Earth.” (Hewitt 2013)

References

Gillespie, Dizzy. Groovin’ High. Savoy 152. 1993 (originally released in 1955).

Hewitt, Michael. “Section 5: Pentatonic Scales.” In Musical Scales of the World, 125-134. The Note Tree, 2013.

Levine, Mark. “Chapter 15: Pentatonic Scales.” In The Jazz Piano Book, 219-237. Petaluma: Sher Music Company, 1989.

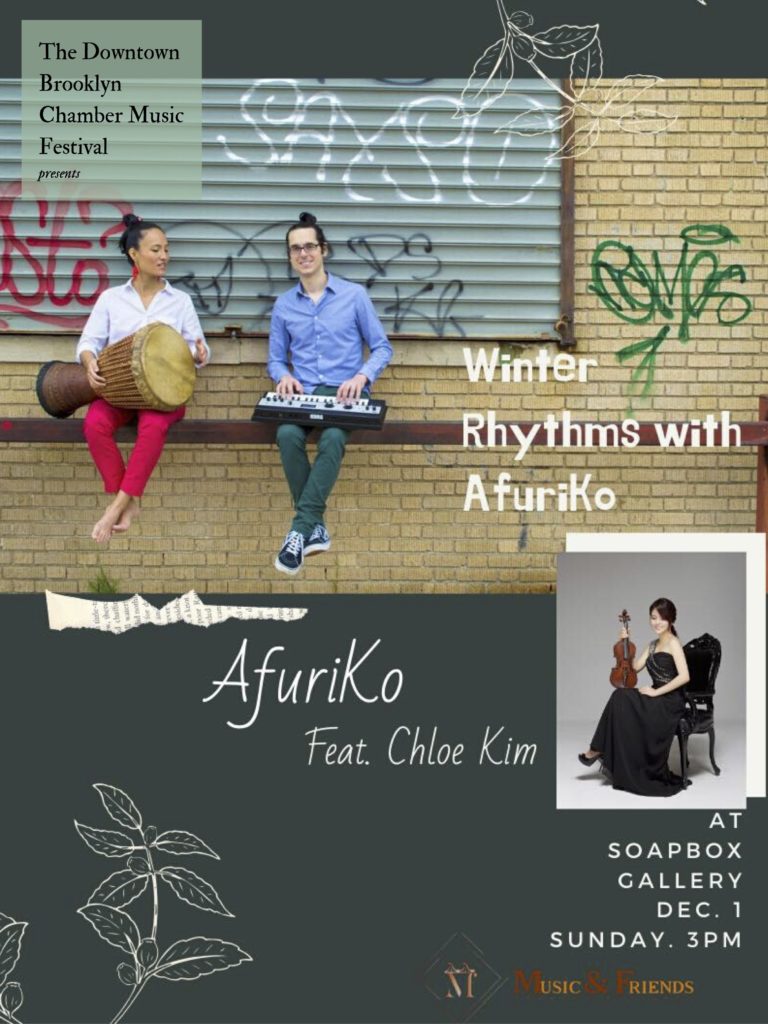

Visit https://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today: