Assuming that the left hand is going to be the weaker hand for most pianists, here are a few tips designed to help you work your way to becoming (closer to) ambidextrous at the piano…

Practicing contrapuntal music

When it comes to putting the left hand on a par with the right, melodically and technically, what better place to start than the music of Johann Sebastian Bach? His Two-Part Inventions are especially well suited for this very kind of practice, each of them being a short contrapuntal piece in a particular key, wherein the left and right hands dialogue elegantly and flawlessly.

Once a few (at the very least) of these Two-Part Inventions have been mastered, why not try out a Sinfonia (Three-Part Invention)? Adding an extra layer of counterpoint that wanders between the inner parts of the left and right hands is indeed a rewarding challenge! And for the bravest and most disciplined among us pianists, there is always the option to tackle a Prelude and Fugue from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier… Or, perhaps a more exotic choice, one of the twenty-four composed by Soviet-Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich.

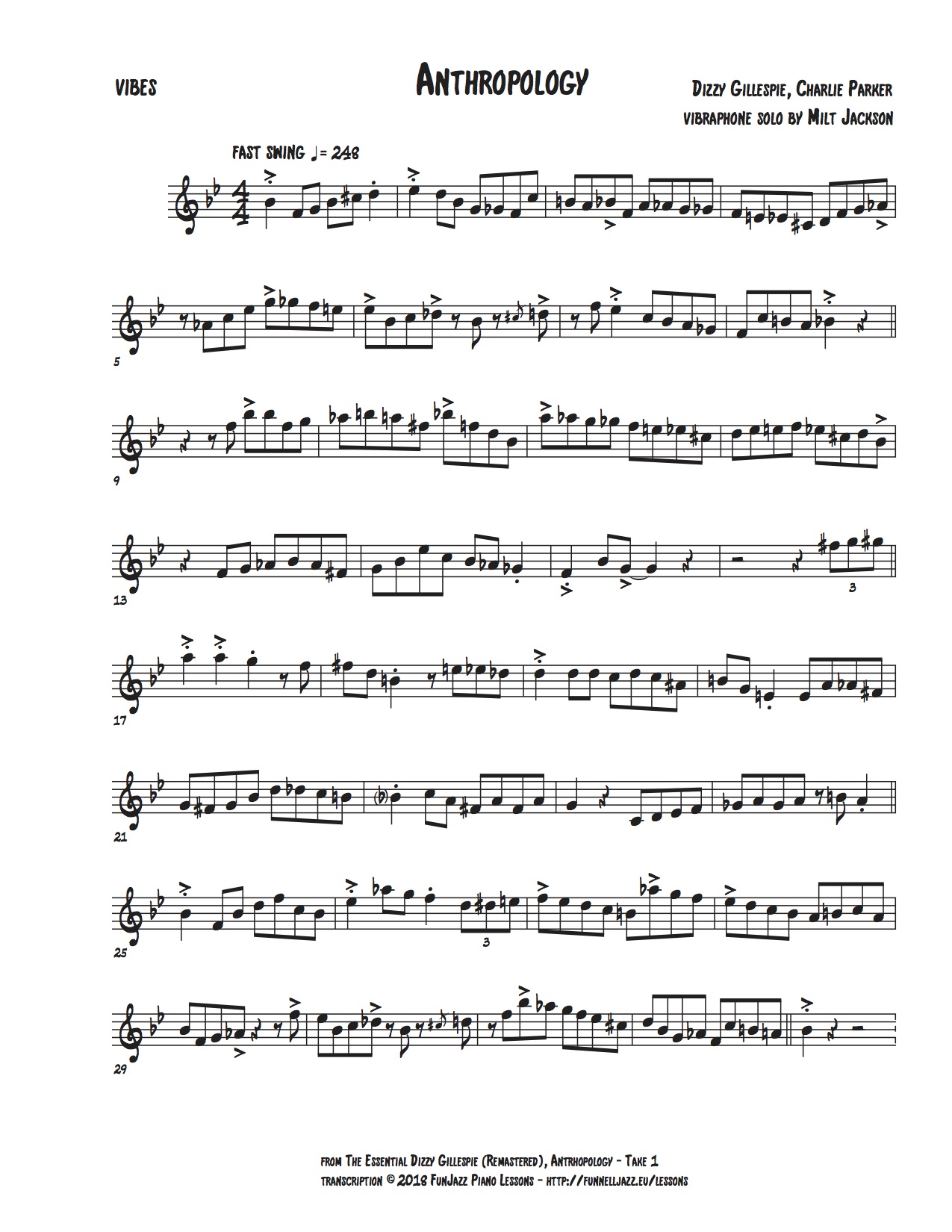

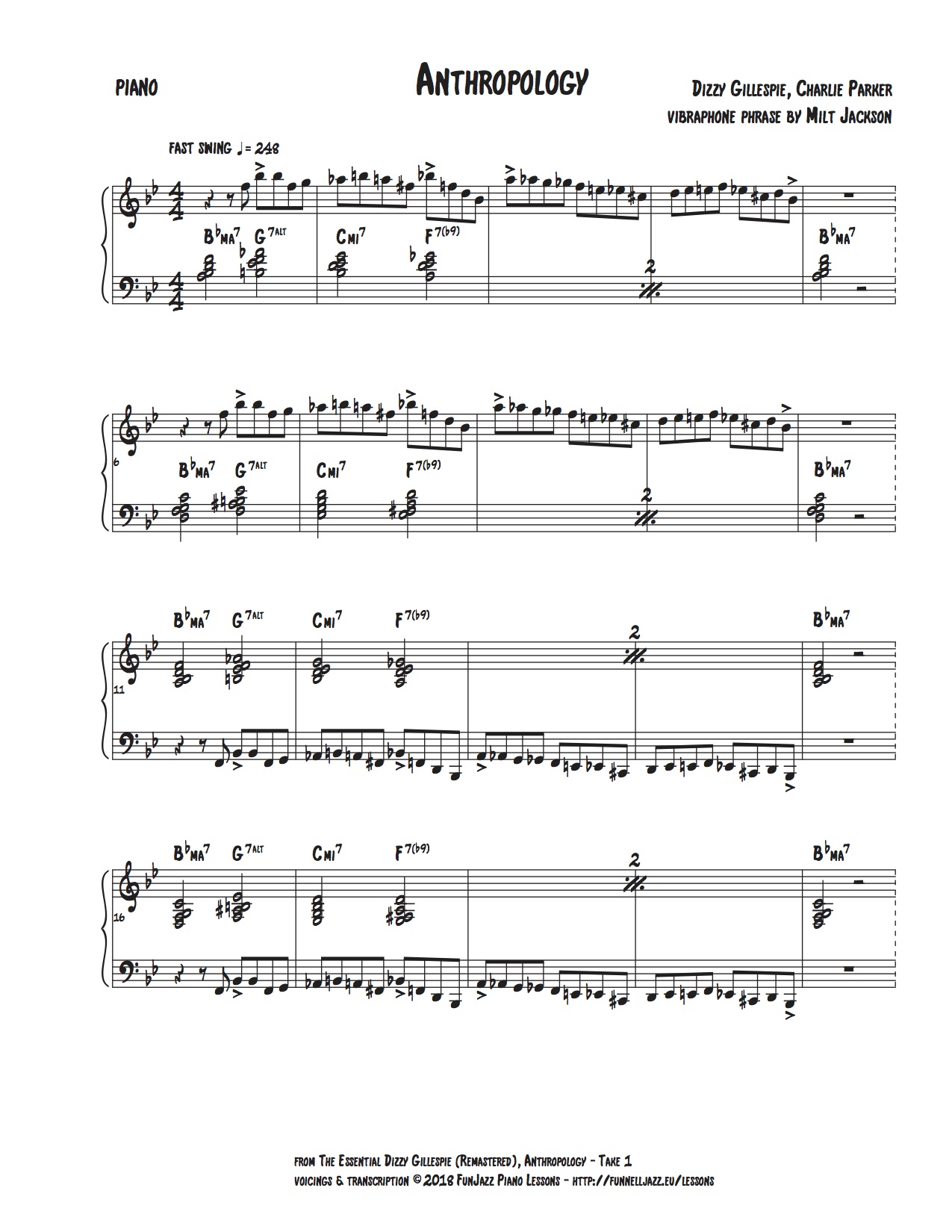

Playing bebop lines in octaves

This type of practice is quite straightforward: along with the blues, bebop is indeed a foundational style for every aspiring jazz pianist. It’s always best to learn the tunes by ear whenever possible. Otherwise, the Charlie Parker Omnibook provides some excellent transcriptions. Pick a tune and practice the head/solo slowly in the right hand then the left, with a click track beating on two and four. Make sure to exaggerate the swing feel (ternary subdivision of the beat and accented upbeats) throughout. Once you’re comfortable playing the lines in each hand separately, go for a more powerful sound/texture and play them both together, one or two octaves apart.

Switching roles between the left and right hands in improvisation

Typically, when it comes to jazz piano, it’s fair to say that melodic lines tend to be played in the right hand, accompanied by chords (2-, 3-, or 4-note voicings) in the left. However, turning this familiar situation around (i.e. reversing the parts played by each hand) on a regular basis when practicing/performing proves to be highly beneficial: a strong left hand is an important feature, adding variety of range and texture. Incorporating this technique into your palette will have the following effects:

- stronger hand independence will be achieved, both rhythmically and harmonically: playing notes other than roots and fifths (and other common chord tones/approaches typically played in bass lines), notably tensions as part of the melody in the low end against the chords higher up in the mid register, can be a novel experience and will have the effect of stretching the realm of what is commonly heard by the ear and processed by the mind.

- it will lead you to use different chords/inversions: sometimes a voicing may be too low and sound muddy when played with the left hand in the lower part of the keyboard, but the same voicing played higher up will sound OK due to the absence of low interval limitations;

- the left hand is generally weaker and slower than the right hand. Such technical restraint will force you to rely more on musicality, inner hearing and singing when soloing with your left hand. Going back to improvising with the right hand will feel a lot easier, musicality now being right at your fingertips, with the greater technical ability of your strong hand available to serve it.

References

Bach, Johann Sebastian. Inventions and Sinfonias BWV 772-801 (Two- and Three-Part Inventions).

Bach, Johann Sebastian. Das Wohltemperierte Klavier Teil I BWV 846-869. Munich: G. Henle Verlag.

Funnell, Jim. New Dream. Funnelljazz FNLJZ 4. 2024.

Parker, Charlie. Charlie Parker Omnibook: for C instruments (Treble Clef), transcribed by Jamey Aebersold and Ken Slone. Los Angeles: Alfred Music Publishing.

Shostakovich, Dmitri. 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87.