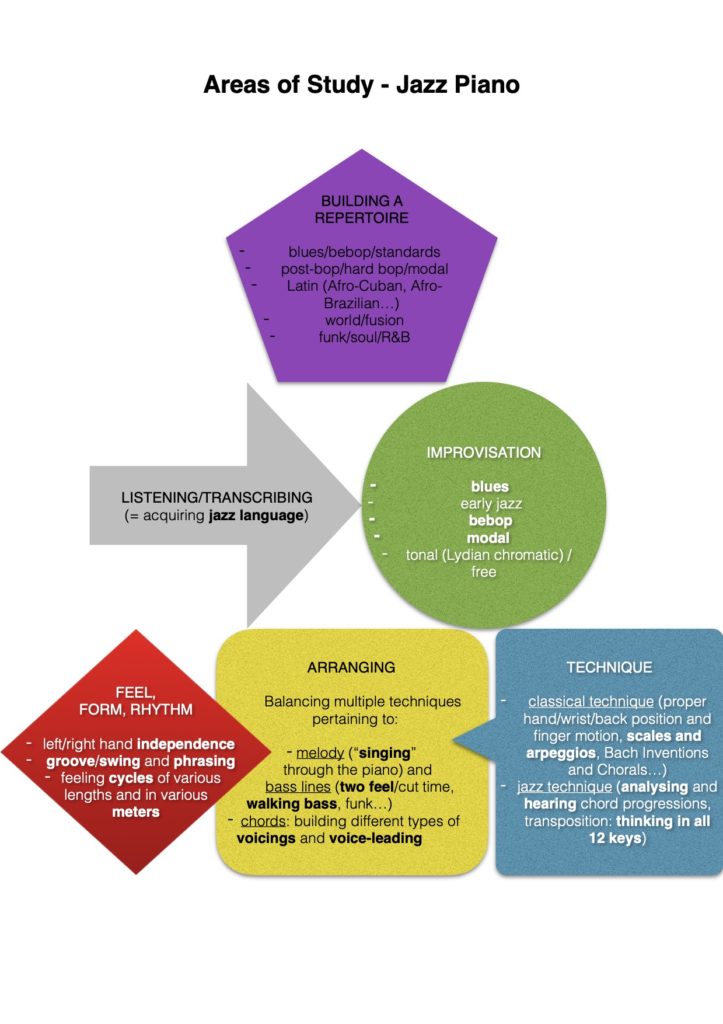

The foundational level

‘Feel, form, rhythm’, ‘arranging’, and ‘technique’ are what I call the three foundational blocks of jazz piano playing. Without them, you won’t be able to build anything musically solid because your playing will always lack rootedness, depth, and precision. To improve in the area of ‘feel, form, and rhythm’, I recommend immersing yourself in some kind of West African musical tradition¹ (Ewe drumming and dance, djembe and dundun rhythms, etc.).

‘Arranging’ is about mastering different textures and telling an engaging story. The piano has an inherent orchestral quality due to its wide range and polyphonic nature, so there is a lot to cover here, from bass lines, to chord voicings, all the way up to how to interpret and embellish a melody.

As far as ‘technique’ is concerned, some sub-areas are specific to jazz (such as practicing a snippet of music in a variety of keys) and others more peculiar to classical performance (using gravity and proper posture to get a great sound out of the instrument for example). This is why I often encourage my students to work on Hanon’s Virtuoso Pianist in Sixty Exercises, and the Bach Chorales² and Two-Part Inventions at the very least (taking separate classical piano lessons altogether, in addition to the jazz piano lessons, being the ideal scenario).

The heartbeat of jazz

These first three foundational blocks support those that make up the second level in the diagram. ‘Improvisation’, in my opinion, is the heartbeat of jazz. It’s at the very core of the music, which itself is all about individuation (or finding your own voice). At its left, you’ll notice that I represented ‘listening/transcribing’ as an arrow pointing towards ‘improvisation’. That is because the jazz language you will be exposed to, and eventually internalize, will unavoidably feed into your personal style as an improviser (Wernick 2010). The elements of tradition and innovation constantly and dynamically coexist in jazz, very much like the yin and yang components of Taoist philosophy.

Culmination

Finally, all five aforementioned blocks support the final block at the top of the diagram: ‘building a repertoire’. Now the good news is: this task should be relatively effortless if you’ve studied all the other areas conscientiously… This culminating block is all about having fun learning the tunes you like, or even writing, practicing, and performing your own!

Notes

¹ I recall from my time at Berklee that such was also Meshell Ndegeocello’s advice.

² Jazz pianist Fred Hersch (2012) also recommends working on the Chorales, and offers a step by step approach to studying them involving pairs of two voices, then groups of three, and finally all four.

References

Bach, Jean-Sébastien. n.d. 101 Chorals à 4 parties réduction pour orgue ou piano. Paris: Editions Durand.

Bach, Johan Sebastian. 1970. Keyboard Music. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

Dahn, Luke. 2021. “The Four-Part Chorales of J.S. Bach.” Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.bach-chorales.com/.

Hanon, Charles-Louis. 1929. Le Pianiste Virtuose en 60 Exercices. Bruxelles / Paris: Schott Frères.

Hersch, Fred. 2012. “Back to Bach: Keys to Jazz Piano Prowess.” Downbeat, September 2012 (pp. 76-77).

Wernick, Forrest. 2010. “The Importance of Language.” Jazzadvice. Posted June 30, 2010. https://www.jazzadvice.com/the-importance-of-language/.

Visit https://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today: