If you’ve ever had a go at analyzing a standard and/or figuring out what scales to use on each chord, the question “So, what exactly is the deal with modes?” might have popped up in your mind. This very question certainly did arise recently during an online conversation I was having with a student of mine, who further developed his concern: “In the key of C for example, all of the modes are made up of the exact same notes (the white keys on the piano)… So why bother learning them!?” That is indeed a good question…

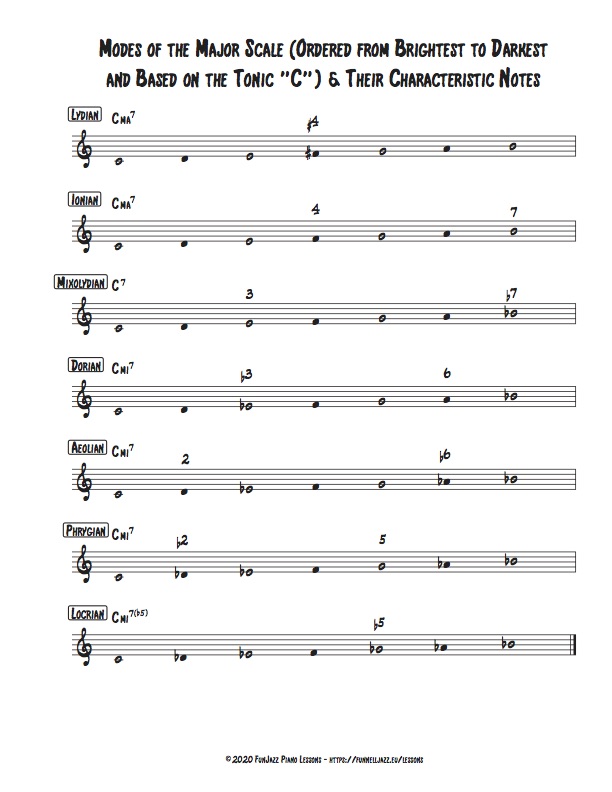

As musicians, we have to remember, and above all experience, that each mode has a distinctive flavor, or color, and conveys a particular mood or feeling. A mode’s particular color is conferred to it by the specific arrangement of intervals within the mode, and the resulting relationship each tone in the mode bears with its tonic. Some tones play a more important role than others in giving a mode its unique color. We call them “characteristic notes.” So let’s have a look in more detail at each mode of the major scale, and see if we can figure out what the characteristic note(s) are for each of them.

The modes of the major scale above are ordered from the brightest or most “major sounding” (Lydian’s intervals are all major or augmented, with the exception of the perfect 5th), to the darkest or most “minor sounding” (Locrian’s intervals are all minor or diminished, with the exception of the perfect 4th). The root C being common to all seven modes, it is not considered a characteristic note (or part of a pair of characteristic notes) for any mode. In order for you to hear the different modal colors, I recorded seven short improvisations on the piano (one for each mode) over a C drone (the tonic, common to all seven modes, played in octaves in the left hand).

Now, when we lower #4 (F#) to 4 (F), we get the Ionian mode.

Lowering 7 (B) to b7 (Bb) gives us the Mixolydian mode.

Lowering 3 (E) to b3 (Eb) gives the Dorian mode.

Lowering 6 (A) to b6 (Ab) gives the Aeolian mode.

Lowering 2 (D) to b2 (Db) gives the Phrygian mode.

Finally, lowering 5 (G) to b5 (Gb) gives the Locrian mode.

Lowering the root by a semitone would give the Lydian mode, but this time constructed with the note B as the new tonic (down a semitone from C). We could go through the same cycle again, outlining all seven modes from the brightest to the darkest, based on B as the new modal center if we wanted to… But by now, I’m sure you got the point!

Practice tips

Just like I did for the recordings above, spend some time with each mode, improvising with it in free rhythm (no regular pulse necessarily needed here). You can explore melodic ideas in the right hand while holding down two Cs an octave apart in the left hand (the drone). Spend 5 to 10 minutes (or more) with a particular mode during each session, and practice different modes based on different tonics every day. Eventually, all 7 modes in all 12 keys (84 in total!) should become familiar musical terrain, but take it easy… day by day and one step at a time! The goal is to internalize them deeply, and fully assimilating one mode in one key will help you assimilate other modes (in the same or different keys) faster.

Then of course, you can start applying them in the context of tunes. Modal jazz tunes such as So What, Impressions, Cantaloupe Island, etc. are a great starting point because they usually feature a slow harmonic rhythm (the same chord spanning a large number of measures) and few different modes/tonic centers. John Coltrane’s Naima is also a great choice with plenty of beautiful modal colors. The harmonic rhythm is faster with this tune though, so take it step by step (1 or 2 bars at a time) and extend the harmonic rhythm if necessary (i.e. play several bars of the first chord, the same number of bars of the second chord, and make a loop out of the two-chord progression; then repeat with the next couple of chords and so on!).

Visit https://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today: