A multifaceted structure

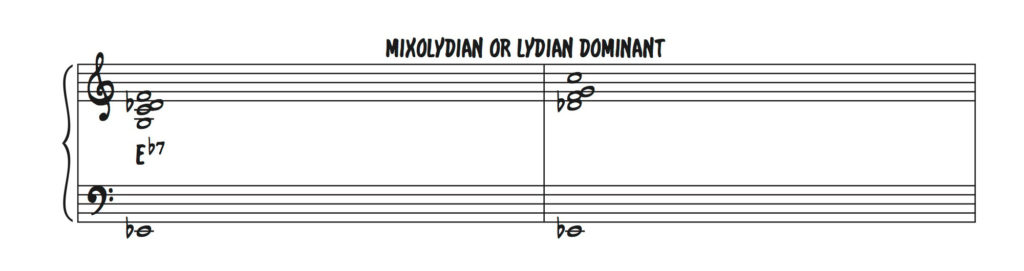

The “dominant shape” is extremely versatile. It can be used to voice chords that are derived both from major harmony, and from melodic minor harmony. The degrees on which each chord mentioned here functions are indicated in the captions below each example. Some of those chords work better in modal contexts (or when one has a vertical approach on each particular chord within a tonal context), and some also sound fitting in various tonal contexts. Let your ear be your guide!

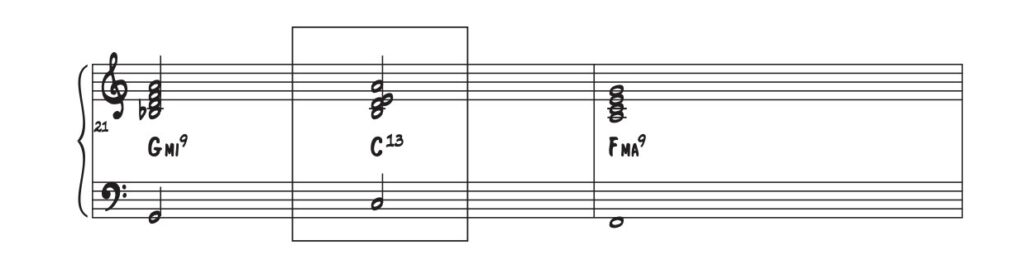

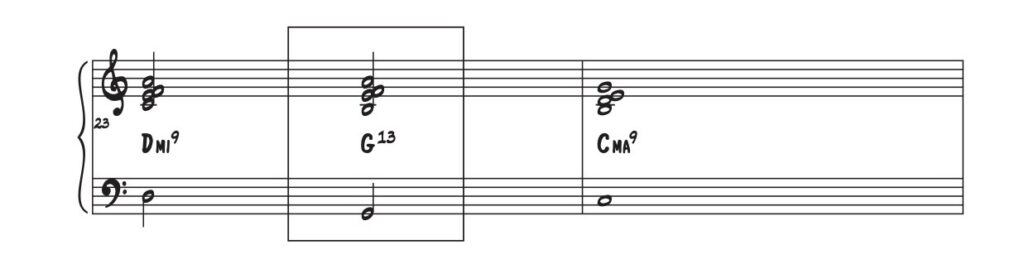

Transposable formulas (specific arrangements of chord tones and tensions, e.g. “3 13 b7 9”) are also given in the captions for each chord (in each caption, position B is listed first and position A second to be consistent with the music notation). By position A/B, it is meant “dominant shape (voicing used for the V chord) extracted from the major II-V-I progression in position A/B.”

The dominant shape is comprised of the following intervals (listed from the bottom to the top of the voicing): major third, major second, perfect fourth in position A / perfect fourth, minor second, major third in position B.

Use cases

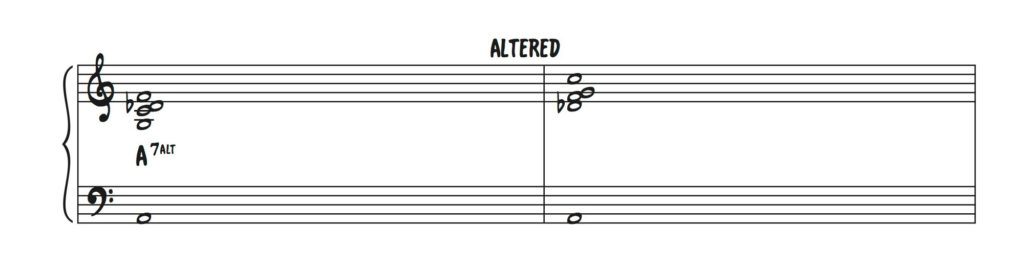

The mixolydian chord is listed here in prime position, since it is, naturally, the one from which the thought of using the dominant shape to play other chords initially came from. As you will see in the first example below, the lydian dominant or 7(#11) chord, from melodic minor, can be voiced in the exact same way as the mixolydian chord (even though the colourful #11 won’t appear in this specific voicing). Then we have the altered chord, and it is interesting to note that there is a sub V (tritone substitution) relationship between the mixolydian and the altered dominant chords. Eb7 and A7alt, for example, indeed share the same guide tones (G and Db/C#), and their roots are indeed a tritone apart. As a result, one chord can be substituted for the other following the tritone substitution rule.

Position B: 3 13 b7 9; Position A: b7 9 3 13.

Position B: b7 #9 3 b13; Position A: 3 b13 b7 #9.

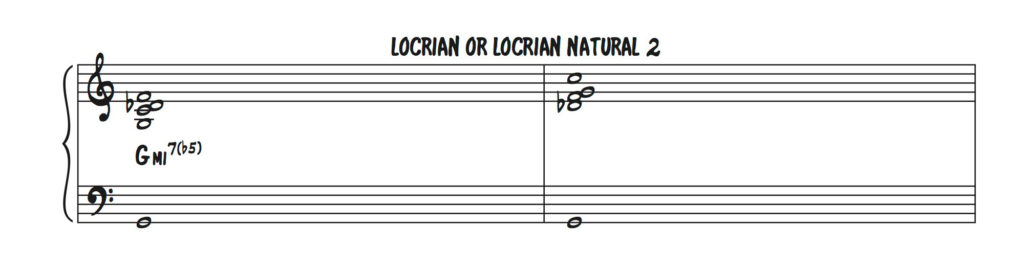

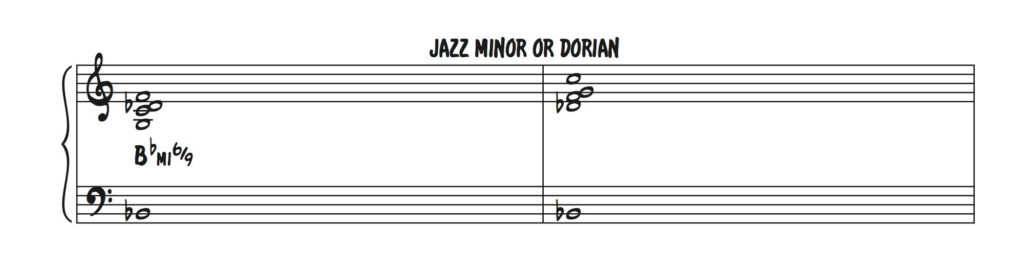

I have then chosen to list the locrian/locrian natural 2 and dorian/jazz minor chords, since they are also widely used. In fact, a minor II-V-I can be played entirely using the dominant shapes presented here (e.g. Emi7(b5) = E A Bb D, A7alt = G C Db F, Dmi6/9 = F A B E).

Position B: 1 11 b5 b7; Position A: b5 b7 1 11.

Position B: 6 9 b3 5; Position A: b3 5 6 9.

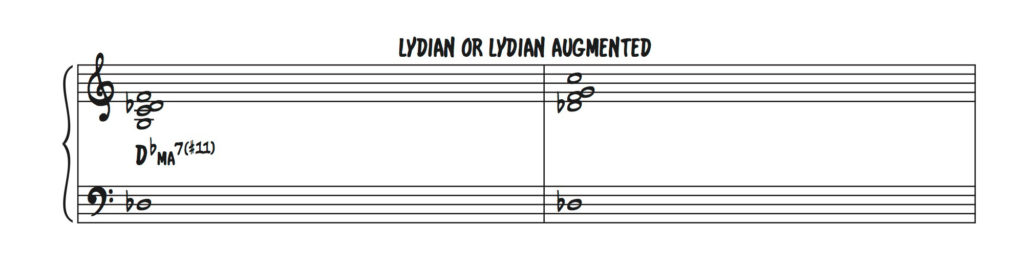

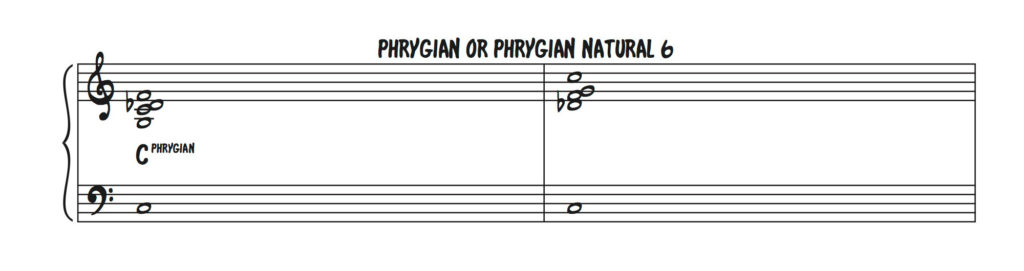

Next up are the lydian/lydian augmented and phrygian/phrygian natural 6 sounds, which also come in handy, albeit arguably more sporadically than the ones mentioned previously.

Position B: #11 7 1 3; Position A: 1 3 #11 7.

Position B: 5 1 b9 11; Position A: b9 11 5 1.

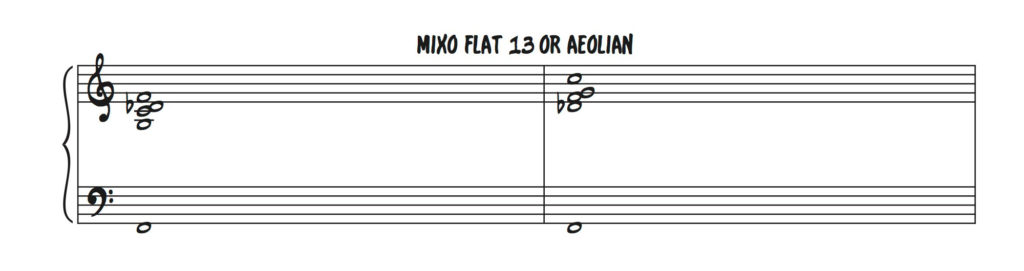

The mixolydian b13/aeolian sound is probably the least common of all (moreover, it is rather tricky to find an adequate chord symbol for it, so the space has been left blank).

Position B: 9 5 b13 1; Position A: b13 1 9 5.

Finally, if the same voicing (G C Db F in position B / Db F G C in position A) were to be played over an Ab root (tonic of the Ab major scale) in order to obtain an ionian sound, the “avoid note” Db might stand out and create havoc, particularly in a tonal context… In a modal/vertical context however, the voicing can be used and sounds quite unique and intriguing.

Practice tip

Internalize both shapes by taking them through the cycle of fifths (using different roots in the left hand for example; that way you’ll get the different sounds described above). It’s fine if you have to think about the formulas at first, but try and gradually shift towards using your ears and muscle memory exclusively. It is without question a challenging exercise… But trust yourself in the process: it will be way more fun!