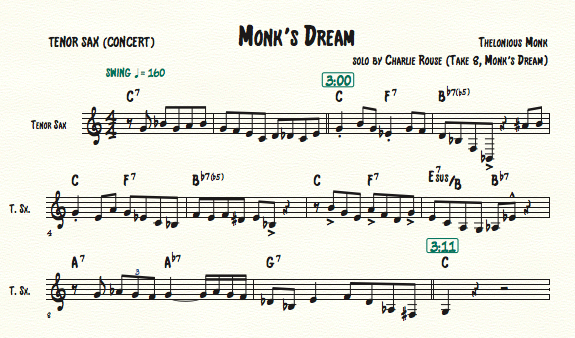

My favourite passage from Charlie Rouse‘s solo on Thelonious Monk’s 1962 recording of Monk’s Dream – Take 8 is made up of the four closing phrases below (Charlie’s final statement right before the piano solo starts):

Most of the soloing is built on chord tones here: the emphasis is placed on the notes that make up the lower part of the changes (root, 3rd, 5th, and 7th) as opposed to the tensions (9th, 11th, and 13th). It is interesting however to pay close attention to the use of nonchords tones, and to the various triads – interestingly all arpeggiated in a descending motion, and mostly in root position (RP) – that emerge to define a distinct melodic contour.

Nonchord tones:

- Db in bar 1 (technically the “second” measure here: the very first measure shows the 3-beat pickup to the first phrase and we’ll number it “bar 0”) is a passing tone approaching the following C from above (upper chromatic approach);

- A# in bar 3 approaches the note B (which, as the major 7th of the following C chord, is itself an example of harmonic anticipation) from below (lower chromatic approach);

- the first E in bar 5 can be seen as a lower chromatic neighbor tone of the two Fs it’s surrounded by, although E is technically the flatted fifth of Bb7(b5), and could arguably be considered a chord tone as well;

- D# in bar 5 is a lower chromatic approach to the following E;

- the notes A (diatonic note to the E7sus/B chord) and G (chromatic note since it doesn’t belong to the E mixolydian scale from which E7sus/B derives) in bar 7 form an diatonic-chromatic enclosure, surrounding the following Ab; such nonchord tones are also commonly referred to as changing tones;

- both Abs in bar 8 are upper chromatic neighbor tones;

- the first F in bar 8 is a lower neighbor of the G, which when struck against the Ab7 chord becomes a bold sounding nonchord tone itself!;

- Ab and F# in bar 9 form a chromatic enclosure of the following G.

Melodic triads:

- Eb+ (RP) over C and F7 (bar 2);

- Bb (2nd inversion) over Bb7(b5) (bar 3);

- C- (RP) over F7 (bar 4);

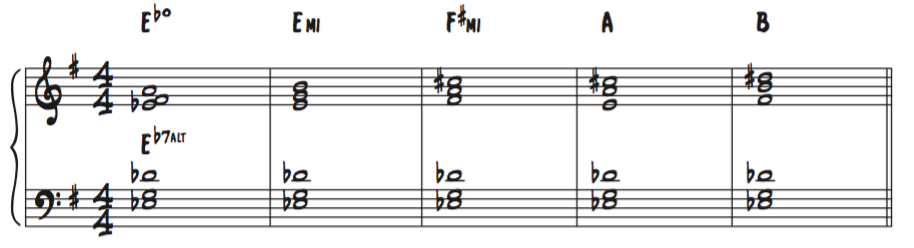

- E- (RP) over C (bar 6);

- D- (RP) over F7 (bar 6);

- C (RP) over F7 and E7sus/B (bars 6-7);

- A- (RP) over E7sus/B (bar 7);

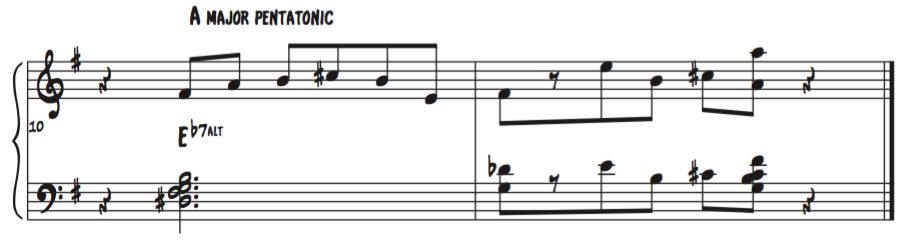

- Bb- (RP) over Ab7 and G7 (bars 8-9);

- Db (2nd inversion) over G7 (bar 8).

Visit http://funnelljazz.eu/lessons/ for detailed information about lessons or click on the image below to book your lesson today: